As current Chair of the Arctic Council, Canada will host the biannual Ministerial meeting in Iqaluit, April 24-25, before handing over the reins to the United States.

Canada has chaired the Council during a particularly fraught time, with geopolitical tensions simmering between Russia and the West over the crisis in Ukraine, and philosophical tensions rising between local and global visions for the Arctic. As Canada prepares for the Ministerial, it is worth reviewing what went well, what went poorly and what to expect in Iqaluit.

The Aglukkaq Factor

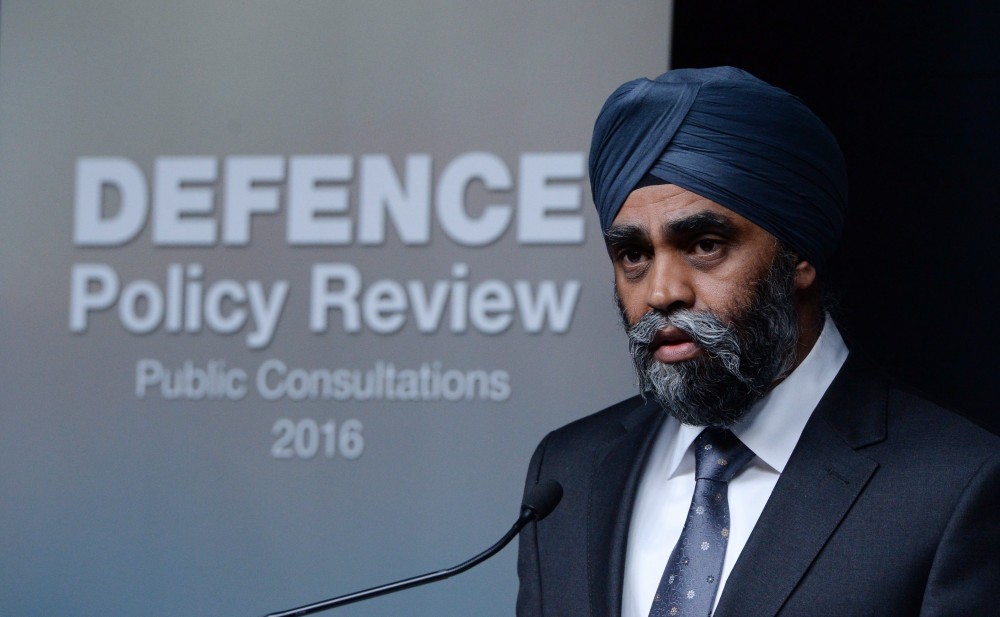

The first indication that Canada’s chairmanship might be a little bit different was in the appointment by Prime Minister Stephen Harper of Minister of Health (now Environment) and Nunavut MP Leona Aglukkaq as Minister for the Arctic Council and Canada’s Chair of the Arctic Council – a role normally fulfilled by the Foreign Minister. Aglukkaq began her appointment by conducting a tour of the territories as well as a handful of Nordic states to consult with Northerners and diplomats and solicit feedback on the Canadian priorities. Announced in November 2012, the Canadian Arctic Council Chairmanship agenda focused on “Development for the people of the North”, with sub-themes of responsible Arctic resource development, safe Arctic shipping, and sustainable circumpolar communities.

While the Arctic Council’s mandate includes both environmental protection and sustainable development, it has historically focused on the former. Canada’s agenda sought to re-emphasize sustainable development – which some critics derisively summarized as (gasp) economic development – and included the establishment of an Arctic Economic Council. This was met with criticism, as some commentators and environmentalists feared the Arctic states were opening up the region to industry and big business.

Aglukkaq was also publicly dismissive about the involvement, alternately, of scientists and non-Northerners in the Arctic. While many in her home territory would echo the sentiment, many (non-Northern) others felt the Canadian Chairmanship was exclusive and parochial, focused on issues that were of interest to Canada domestically and Aglukkaq personally to the detriment of the many issues the forum had developed expertise and success with over the course of 15 years.

Other than the establishment of the Arctic Economic Council – and your air must be pretty rarefied if you believe business and economic development have no legitimate place in the Arctic – these worries have proven unfounded, and business as usual has reigned in the actual work of the Arctic Council. It is dominated, after all, by working groups and task forces that focus on environmental protection. More to the point, Aglukkaq has barely been heard from for the past two years. Some may have hoped, or expected, that she would be a powerful Ambassador for the people of the Canadian Arctic and Circumpolar North, speaking at events and conferences, communicating the Arctic experience, expounding on her vision for the region and building political will for better or faster change. They will have been disappointed.

Aglukkaq is ending her Chairmanship as she began it, with a tour of communities in Nunavut and NWT. But she has squandered the opportunity afforded by her position of improving Canada’s reputation and solidifying its status as a leader in Arctic affairs.

The Bear in the Room

Of greater interest to the popular media has been the impact of Russia’s conflict with Ukraine on Arctic politics and regional relations. The crisis began half way through the Canadian Chairmanship, and just weeks before a Senior Arctic Officials meeting was scheduled in Yellowknife. Canada had placed travel bans on some Russians and had the legal ability to exclude the Russian Senior Arctic Official in this case – but didn’t. The meeting proceeded as planned, with Russian involvement, as have two other SAO meetings since. No doubt the consequences of the Ukraine conflict has been a topic of personal discussion amongst Arctic diplomats, but publically it has not featured.

In fact the Arctic Council has remained very well insulated from broader geopolitics, with two relatively minor exceptions. Canada and the United States opted out of an Arctic Council Task Force meeting (on Black Carbon and Methane) as it was held in Moscow, on April 14-15, 2014, however there is little indication their absence impacted the work of the group significantly. Three more TFBCM meetings in the six months subsequent enjoyed full participation from all Arctic member states. There are dozens of Arctic Council SAO, working group, task force and expert group meetings every year and this was the only one to be directly affected.

Perhaps more notable was the recent announcement by the Russian Embassy in Ottawa that Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov would not be attending the Ministerial in Iqaluit due to “prior commitments”. Russia will instead be represented by its Minister for the Environment, Sergei Donskoi. Lavrov has attended every Arctic Council Ministerial since 2004 and there should be no doubt that his absence is related to recent tensions with the West and particularly Canada’s aggressive rhetoric over Ukraine. Although all parties are committed to maintaining cooperative relations within the work of the Arctic Council – where conveniently Canadian and Russian interests align – the prospect of a high level meeting was too much to bear. Canadian officials had already cancelled the Arctic Council events that were to be held in Ottawa the day before the Ministerial – organized to accommodate the many Observers and representatives who could not logistically be included in Iqaluit – to avoid a scene where official Canada was seen to be feting the Russians right in the nation’s capital, in contravention to their ‘principled stance’ elsewhere.

Lavrov’s absence will have mostly symbolic impact, as Russia, like Canada, will still be represented by its Environment Minister, and the move has not been trumpeted as a boycott or political statement. Indeed Russia announced the news on the Orthodox Easter holiday, presumably to tame speculation and fuss about Lavrov’s motives. The main output of the event, the Ministerial Declaration, is almost wholly drafted weeks and even months in advance and will have been agreed upon by the states and Permanent Participants beforehand. The decision seems to have everything to do with Ukraine and nothing to do with the Arctic Council.

It’s further worth noting that Russia continues to co-chair two of the three Arctic Council task forces and participated in the first Arctic Coast Guard Forum experts’ meeting in Washington last month. If this is the extent of the geopolitical spillover we can expect into Arctic affairs, it will confirm the Arctic region’s exceptionality in international relations.

Canada’s Record

Anecdotally, Canada’s Arctic Council Chairmanship has been mired in malaise, from criticism of the Arctic Economic Council to original SAO Chair Patrick Borbey’s untimely departure, and from the “boycott” of the Moscow meeting to general dissatisfaction with the Canadian management of the Council’s work. But objectively it is hard to see the Canadian Chairmanship as anything but a continuation of the Arctic Council’s record of success.

The Council is busier than ever. Its tasks forces have proven productive, the working groups continue to provide world-class scientific recommendations and increasingly work on implementation. The management and communications of the Council have improved with the new Secretariat, and the influence of the Permanent Participants is stronger than ever. Indeed the list of activities undertaken in the past two years is so long that it would be tedious to outline here (much of it is publically available in the Arctic Council documents section).

Ministerial deliverables are likely to include a non-binding framework plan on oil pollution prevention; a Framework Document on Black Carbon and Methane, with quantitative goals to come later, in 2017; an Arctic Marine Strategic Plan for 2015-25; and recommendations for incorporating traditional and local knowledge into the work of the Arctic Council. This is not breathtaking stuff, but it is entirely conventional. The Canadian Chairmanship has been much more like other Chairmanships than it has been different.

Let’s See if You Can Do Better

If the means justify the ends, then Canada’s Chairmanship can be hailed a success. Those who resent the Conservative’s foreign policy under Stephen Harper will find faults with the Ministerial and its outputs, but let them try to show objectively, and quantifiably, how it is lacking compared to its predecessors.

Still, it has been painful to watch at times, particularly as a Canadian. If the work of the Council has gone ahead unmired, it has as often as not been despite Canada’s leadership of the forum.

If misery loves company, though, it is reassuring to watch the United States go through many of the same growing pains as Canada suffered in its first Chairmanship year. The US seems to have learned all the wrong lessons from Canada’s mistakes, and a rift between Republican Alaska and Democratic Washington DC has emerged. Admiral Papp is working diligently to navigate his way through the melee.

He needn’t work too hard; almost certainly, the Arctic Council will find a way to isolate itself from the politics.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: The Third Wheel: Observers in the Arctic Council, Blog by Heather Exner-Pirot

Denmark: Nordics to step up security cooperation on perceived Russian threat, Yle News

Finland: Survey – More than half of reservists in Finland pro-Nato, Yle News

Norway: Peace and stability crucial for Arctic economy, Barents Observer

Russia: Fire-struck nuclear submarine to be repaired, Barents Observer

Sweden: Russia concerned by Finland, Sweden moves towards closer ties with NATO, Radio Sweden

United States: Arctic priorities questioned on eve of U.S. chairmanship, Alaska Public Radio Network

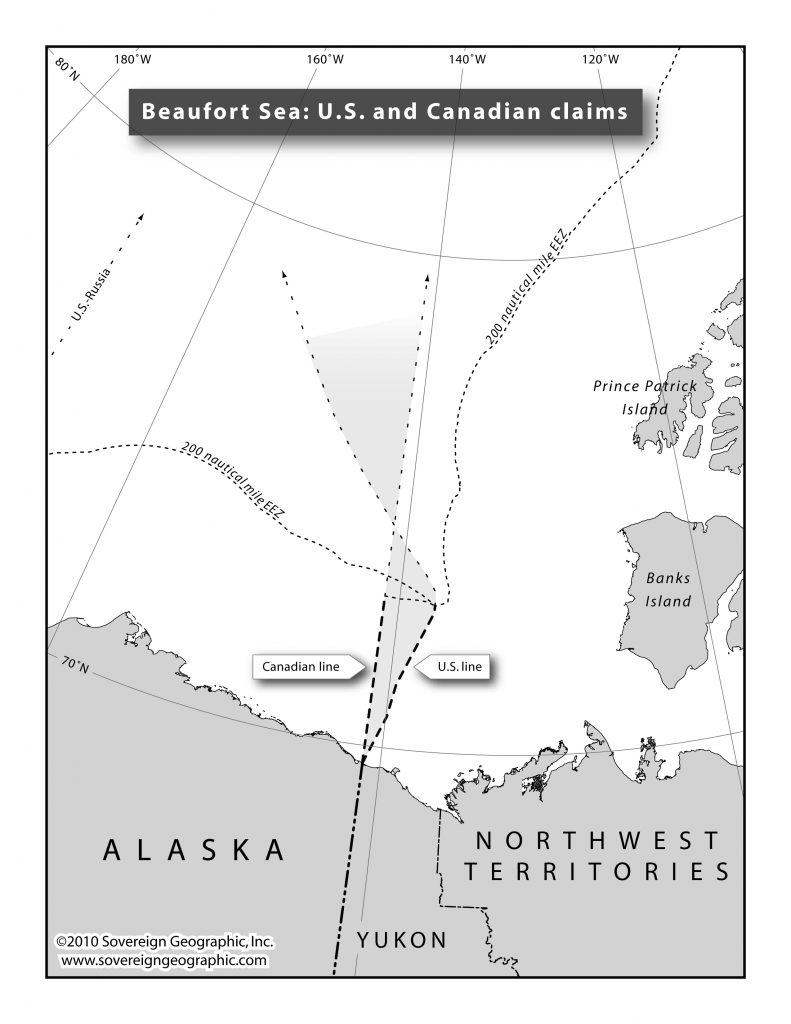

Byers said he was critical of the map of Russian military assets presented by Senator Sullivan, arguing the Department of Defense has produced a more objective assessment of the situation in the Russian Arctic.

Byers said he was critical of the map of Russian military assets presented by Senator Sullivan, arguing the Department of Defense has produced a more objective assessment of the situation in the Russian Arctic.

+

+ shared interests with Foreign Minister

shared interests with Foreign Minister